Editor’s note: The story was first published June 18, 2000 in the Walworth County Week

Written by Linda Godfrey, photographs by Dan Plutchak

In a perfect world, one without racism, there never would have been a need for the neighborhood set on the western edge of Walworth County that’s known as Lake Ivanhoe.

Nonetheless, the residents of Wisconsin’s only black-owned (now partially integrated) community are happy they have this quiet place to call home.

Originally designed early in the last century as a country haven for well educated, prosperous black Chicagoans, its rustic surroundings still provide a measure of peace for those who live there.

The population of the subdivision located on the southeast shores of the 52-acre lake was about 150 in 1995.

That figure included about 75 households, with an additional 30 houses used only seasonally. And those who come here for a change from city life do find what they are seeking.

“I had to get used to not having sidewalks or streetlights,” said Jeannie Collier from the porch of the cottage she and her husband Willie built in 1965. “I had to get used to well water, too. But I love it.”

The Collier’s main residence is in East Chicago, Indiana, but they’ve been coming to Lake Ivanhoe for weekend and summer vacations with their children for the past 35 years.

They heard about Lake Ivanhoe from a relative, said Jeannie, and decided to take a drive there on a whim, to try out a new car.

“A friend told us this property was for sale,” she added, “so we bid on it and got it. We just started working on it when we had time.”

Luckily for the Colliers, their son Eric is a skilled construction worker and has been willing to devote his own vacation time to updating and finishing the cottage’s exterior with cream brick and fieldstones found on site. “Our other children don’t come up very much,” said Jeannie. “They’re busy with their own lives and own houses.”

That’s a common refrain heard throughout the subdivision. Many of the original owners have died in the past two decades, and their children have spread out to bigger cities where there are more job opportunities.

Lake Ivanhoe was intended to be the equal of Lake Geneva in the dreams of those who planned the community, with first-class resorts, restaurants and lake facilities. But it didn’t exactly turn out that way, and the story of its struggle to exist on its own terms is the equal of any civil rights saga in America.

One of the community’s true activists still lives in the tiny yellow house where she and her husband raised their children. Nettie Hatters’ main battle these days is against a debilitating case of asthma, but she remembers the days when it was hard just to get basic services enjoyed by the mostly white towns surrounding Ivanhoe.

Residents had to drive to Beloit for haircuts and had trouble getting appliances and other things delivered.

“I’ve been here for 50 years,” she said proudly, surrounded by the medicinal paraphernalia she needs to breathe. “I met my husband in Cleveland. We married and moved here; he already owned the land.”

Over the years, Nettie worked in food services at Lakeland Hospital, the first black person hired there, and then drove a school bus around the Lake Geneva area for 22 years.

“It was a nice place to raise my daughters,” she said.

One girl now works as a counselor for Walworth County, and the other works as a beautician while studying for a career in a medical field.

But Nettie remembers a time when Ivanhoe residents could not get served at area restaurants, much less find jobs here.

“When I first came to Wisconsin,” Nettie remembered, “there was a sign at Paddock Lake (a community east of the Lake Geneva area) that said “No Jews or negroes allowed.”

Nettie especially recalls a pivotal incident in the ’60s when Louis Armstrong was appearing at Lake Geneva’s Riviera.

When it came to Nettie’s attention that the Riviera was refusing blacks admittance to see this legendary black performer, she decided something had to be done.

A white friend of hers called and got tickets, and the two women went there along with Nettie’s husband, Dave.

The doorman would not let them in and called the manager who personally tried to get the trio to leave.

“He said there was two kinds of people he did not want in the Riviera,” said Nettie, “and that was black people and poor white trash. I said well this black person is going in there, or it will be known all over the United States about Lake Geneva, Wis. And he let us in, but he still would not serve us.”

Somehow, Nettie managed to talk with Louis Armstrong himself about the situation.

“He said that guy lied to him about playing for a mixed audience,” said Nettie. “So Louis threatened to load up his buses and leave. All our lives we had to fight like that.”

In fact, the incident inspired the Hatters to call on both the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People) and the state’s Department of Industry, Labor and Human Relations.

Lawyers were hired to confer with Lake Geneva city officials and Riviera management, and the next year Ivanhoe residents were able to attend the Armstrong concert without any trouble.

By 1963, Lake Ivanhoe had its own NAACP chapter, with a firebrand named Ernestine Grace as its president and Nettie Hatters as vice president.

Mastering the history of this and more is recounted in the master’s thesis of a Lake Geneva middle school history teacher, Sam Gonzales. (Editor’s note: Gonzales passed away in 2013 at the age of 67).

Gonzales, a Beloit native who graduated from UW-Whitewater in 1968 and then practice-taught in Lake Geneva, recalls a school supervisor who told Gonzales he’d like to hire him “because I looked like I’d be a good teacher.” Gonzales did end up taking the job and has been there ever since.

But to his surprise, he said, after he was hired, another new teacher, an African American woman, walked up and informed him that his job was supposed to have been hers.

“I found out after I took my job,” said Gonzales, “that Doris Baker had applied for it and been denied, so in order to resolve the conflict they hired me, a Mexican American who ‘looked right.’ ”

Baker had taken her complaint to the NAACP, which met with the school board, and was promised that she’d be given the next job she was qualified for.

The board kept its word, and Baker enjoyed a successful career in that district.

Moreover, she and Gonzales became friends.

Baker lived at Lake Ivanhoe, and when Gonzales mentioned he was looking for a subject for his master’s degree thesis, she suggested Lake Ivanhoe would be perfect.

“I said, ‘What’s Lake Ivanhoe?’ ” said Gonzales.

Once he found out, he agreed.

“She started introducing me to people and I made appointments and calls and began to interview these folks, all very well-educated and nice people,” said Gonzales.

And so it is that Sam Gonzales is now able to tell anyone who will listen just how this special community came to be.

“The story begins with World War I,” said Gonzales, comfortably settled on the front porch of the rural Elkhorn farm house he shares with his wife and fellow teacher Karen and their children.

“There was a shortage of labor in the north and at the same time there was a downturn in the agricultural market in the south, which displaced a lot of black workers.” These workers began streaming into the northern cities, said Gonzales, which already had established communities of professional, educated black people.

As the southern blacks began crowding into the cities, the northern blacks who had previously established themselves there felt a cultural gap between themselves and these newcomers.

They soon began trying to move their families out of their old neighborhoods, because of overcrowding and due to their inability to relate to the less educated, rural blacks.

But even though they were professional, working people they were not welcomed in all parts of the city, and racial tensions began to rise.

“In 1919,” said Gonzales, “there were riots in Chicago at the 29th Street Beach. Some white youths threw bricks and rocks at some black youths who had accidentally floated across the beach’s invisible racial boundary on a raft, and one of the black youths was hit on the head and drowned. Some black citizens apprehended the perpetrators and held them for the police, then watched in dismay as they were arrested and the white youths let go. The riot lasted 4- 5 days.”

There were three men, said Gonzales, who observed all this and decided they had to find someone who would help them make a safe place for their children by buying lake property.

“Jeremiah Brumfield was a Cook County asst. state’s attorney,” said Gonzales, “Bradford Watson was a political activist and worked for city hall, and Frank Anglin worked as a manager at Harvey Motor Truck Works.”

The men contacted a Chicago real estate agent named Ivan Bell, who began to make inquiries into Wisconsin lake properties.

Bell focused on Walworth County, since it was on the Illinois border, and his efforts did not go unnoticed by area residents.

The Elkhorn Independent ran a story on June 4, 1925, headlined “Negroes buy Ryan’s Lake Land This Week— Subdivision.”

It went on to say, “Ryan’s Lake, the old fishing ground for residents of Lyons will be in the possession of Negroes within a few days. Six hundred acres of land have been sold on the shores of this lake for $60,000 to Bradford Watson and Jerry M. Drumfield (sic), Chicago Negroes, who will subdivide the land for lot sale at $100 to $1,000 a lot. Seventy acres of the land is heavily wooded. The new owners plan to dam the lake and thus enlarge it. ”

It was July, 1926, when 83 acres became the property of the Lake Ivanhoe Realty Corporation, according to Gonzales.

The former Ryan’s Lake was named Ivanhoe in honor of Ivan Bell, and the project was jump-started by building a huge pavilion overlooking the lakeshore.

Frank Anglin’s wife, Espy, described it as the “largest or second largest pavilion in the state of Wisconsin. A big dance floor with a veranda all the way around it, they had a soda fountain and a snack bar up near the front and a restaurant in the back. They made a beach and it had a nice pier with a high dive.”

The pavilion also boasted a water system, indoor plumbing and electrical generators and a marble bar.

For its opening night, the promoters brought in Cab Calloway and his band, and Ivan Bell hired taxis to bring prospective buyers from Chicago for the evening.

The grand plan worked, people started buying lots, and a Lake Ivanhoe land boom began.

It seemed Watson and Brumfield’s dreams of a grand resort for black people was becoming reality.

“But in 1929,” said Gonzales, “the Great Depression hit, and black people were some of the first to lose their jobs. Had the Depression not happened, they probably would have made it exactly what they wanted it to be.”

However, money now being in short supply, sales fell off and there were attempts to buy the land back from the black consortium.

“But the black people weren’t going to leave,” continued Gonzales, noting that they somehow managed to cling to the bulk of their property even when times got hard. Life in the country ollowing that,” said Gonzales, “Lake Ivanhoe languished until the 1970s. Then resident Harrison Bailey attempted to get the state to rehabilitate the lake.”

An article in the Lake Geneva Regional News featured a photo of Bailey and his wife next to the lake, and estimated 50-75 percent of the lake’s original size had been destroyed by weed and silt buildup over the years.

The newspaper quoted John Planke, Walworth County’s Conservation officer at that time, as saying the Ivanhoe residents “faced a seemingly impossible task.”

He turned out to be right. The lake never received any money for improvements.

The newspaper also mentioned at that time that Ivanhoe was one of the best fishing lakes in the state, “one of the few that has no pollution by sewage or water.”

Visitors to the Ivanhoe lakeshore will notice right away that it differs from all other lakes in the county in that it is not completely engulfed by a ring of cottages around its shores.

The Ivanhoe streets are laid out in an orderly grid perpendicular to the lakeshore.

The beach is still there, along a gravel drive, as are the wooden steps that used to lead up to the pavilion, which is long since gone.

A park stands where the old pavilion once was, with a clubhouse of recent vintage nearby.

A property owner’s association keeps the lakefront and buildings in order.

At one time, noted Gonzales and various residents, there was also a lodge in the community used mainly for entertainment purposes.

“At the time I did my research, a lot of the founders were still alive,” said Gonzales.

Gonzales became friends with many of the residents, and was elected as head of the area’s Human Rights Association.

“When anything happened, they’d send me out,” said Gonzales, “and Nettie was always right behind me.

I believed it was the right thing to do because they didn’t have the chance to be part of the community the way they should have been.

I was honored to do that, and that they welcomed me into their homes.”

One woman Gonzales remembers in particular was Sweet Pea Henderson, whose husband was a member of an all-black firefighting unit in Chicago.

“She was one of the community’s shining stars,” said Gonzales. “Thousands of persons have experienced acts of kindness from her while she lived in a cottage at Lake Ivanhoe.”

Many newspapers wrote articles about Sweet Pea, who corresponded with everyone from national and state government officials to newspaper columnists.

“She always tried to write when people were ill to bring them cheer,” said Gonzales. “She had notes from Sen. Robert Kennedy, Claire Boothe Luce, Pearl Bailey and Richard Dailey, to name a few. She reached for her pen and reached out to others. She was The community is still ‘alive and kicking’ the kind of person that all the people were that I knew from Lake Ivanhoe,” he added.

“Open, graceful and polite.”

Sweet Pea, who was born in 1895, died about 10 years ago, Gonzales estimated.

It’s not as if the Ivanhoe community itself isn’t still alive and kicking, though.

In fact, for some Ivanhoe residents, the area is now a little more densely populated than they’d like.

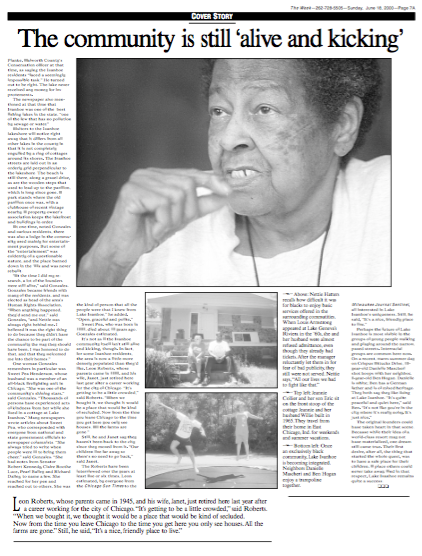

Leon Roberts, whose parents came in 1945, and his wife, Janet, just retired here last year after a career working for the city of Chicago.

“It’s getting to be a little crowded,” said Roberts. “When we bought it, we thought it would be a place that would be kind of secluded. Now from the time you leave Chicago to the time you get here you only see houses. All the farms are gone.”

Still, he and Janet say they haven’t been back to the city since they moved from it.

“Our children live far away so there’s no need to go back,” said Janet.

The Roberts have been interviewed over the years at least five or six times, Leon estimated, by everyone from the Chicago Sun Times to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, all interested in Lake Ivanhoe’s uniqueness.

Still, he said, “It’s a nice, friendly place to live.”

Perhaps the future of Lake Ivanhoe is most visible in the groups of young people walking and playing around the narrow, paved streets.

Interracial groups are common here now.

On a recent, warm summer day on Crispus Attucks Drive, 10-year-old Danielle Mascheri shot hoops with her neighbor, 9-year-old Ben Hogan.

Danielle is white; Ben has a German father and is of mixed heritage.

They both say they like living at Lake Ivanhoe.

“It’s quite peaceful and quiet here,” said Ben.

“It’s not like you’re in the city where it’s really noisy. It’s just nice.”

The original founders could have taken heart in that scene.

Because while their idea of a world-class resort may not have materialized, one dream still came true.

Their first desire, after all, the thing that started the whole quest, was to have a safe place for their children.

A place others could never take away.

And in that respect, Lake Ivanhoe remains quite a success.

.

.